The development of crafts in Sarajevo began immediately upon the arrival of Turks, the Ottomans, in our region. It is well-known, however, that Sarajevo, as an urban centre, began to be developed at location of medieval settlements in 15th century.

Foundations of the economic centre of „seher“ (Persian shahr, a city or metropolis) were laid by construction of the Emperor's mosque, along with the administration court dubbed „saraj“, „musafirhana“ (Persian/Arabic musafirkhana, an inn for travelers), tekija (Sufi 'monastery'), and all other objects, ordered to be built by Isa-bey Ishakovic.

Crafts began to develop for needs of the army and because of construction and maintenance of new buildings. The Ottomans themselves were the ones, who had already had urban civilization and its craft guilds, and who laid the foundations for development of crafts and the Bascarsija. Many crafts in our city developed up to the level of perfection and remained deep-rooted here, thus we may regard it as our own tradition.

The first crafts are mentioned in the oldest known cadastral registry from 1489.

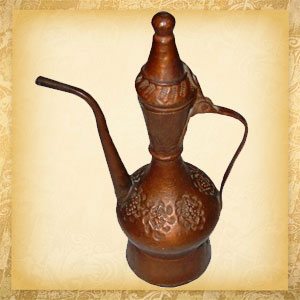

This document shows us that the earliest crafts to appear were those that served the needs of the army, such as blacksmiths, sword smiths, boot-makers, leather-workers, blanket-makers, wool-workers, as well as butchers, bakers and boza-makers. Thirty years later, the number of crafts had more than doubled. Nineteen new crafts are mentioned in the registry from 1528-1536, including shoeing smiths, locksmiths, building traders, woodworkers, cooks, goat's hair workers, coppersmiths, silversmiths, slipper-makers, etc. In the early seventeenth century there appeared bell-makers, steelyards, watchmakers, quilt-makers, cloth-makers, comb-makers and many others. By the end of the nineteenth century about seventy different crafts were mentioned, with some 400 different products. The most numerous were the goods produced by saddlers, coppersmiths, and blacksmiths. Certain crafts reached a high level of real artistic value and were known and appreciated throughout the empire. This was particularly case with coppersmiths, furriers, the filigree-makers, who produced their goods and exported it. Craft shops were partitioned in the Bascarsija. Each craft or similar crafts had its own street or more streets. The saddlers, for example, were all located in the street dubbed Saraci, while streets of butchers, 'sagrdzije' (they scrape fur from cow-hides) and blacksmiths were located around the Cekrekcina mosque. The tailors’ street was located in the area from the Latin bridge (Princip's bridge) toward the today's pharmacy and the sword smiths’ street was in today's Zelenih beretki Street. Many names of streets have been preserved up to nowadays, such as Curciluk, Kazazi, Mudzeliti, Kazandziluk, etc.

Bakers, groceries and coffee-sellers did not have their own streets, since their shops were located throughout the entire Bascarsija.

During the Ottoman period, the craftsmen were organized into esnafi or guilds. All craftsmen, who were engaged in the same or cognate craft, were in the same guild. Each guild had its own board and was completely independent from every other guild. Each was headed by a chief („cehaja“) elected by the craftsmen and their assistants (journeymen), and chief was a connection between the craftsmen and the governing authorities. If he did not do his duties efficiently, he could have always been dismissed. There were strict rules in the guilds. Solidarity between the craftsmen was also well-known, thus, if one craftsman sold something and his neighbor didn't, the first one would send his customer to the one who did not sell anything, explaining that he does not have that product for sale or it was not good enough.

The guilds consisted of members of all confessions, but only a Muslim could be the chief.

They organized religious ceremonies separately, but „kušanme“ (excursions at which apprentices were pronounced as craftsmen) were held jointly. All four religions were presented in the goldsmith's guild; there were Muslims, Catholics and Orthodox Christians in the blacksmiths’ guild, the haberdashers’ guild had Muslims, Orthodox Christians and Jews, and the furriers' guild had a few Muslims, while majority craftsmen were Orthodox Christians, etc.

During the Ottoman period, crafts were the main economy branch, on which majority urban population lived. By the arrival of the Austria-Hungarians, the old crafts faced very difficult period. Some crafts began to stagnate during the Ottoman period, either because of lack of forces which would continue the work, or because of introduction of new, modern technologies for manufacturing of certain products.

With the arrival of new authority, new roads were opened and manufactured goods, that were significantly cheaper than craft products, appeared on the market.

Lifestyle and cloth fashion also changed, thus some old crafts began to disappear.

Sword smiths, gunsmiths, cutlers gradually disappeared. By appearance of fabric materials, weavers disappeared as well as blanket-makers, „kečedžije“ (they made saddles from cow-hides' fur), haberdashers, while furriers disappeared completely, for which Sarajevo once had been famous by far.

Only names of streets in which these crafts were located remained to remember us on it.

From the other side, many crafts have been adapted to the time, becoming modernized and surviving in this way. New crafts emerged as well, thus we have shoe-makers, tailors, lathe operators, electricians, and mechanics of various kinds. The Austria-Hungarian authorities were, however, concerned to preserve some of the old skills. In 1892 the National Government founded several workshops for the old crafts: a carpet-weaving workshop, a workshop for art crafts, and an embroidery workshop. Beside these workshops, the National Government also tried to assist other crafts by opening of vocational schools and courses.

The unwritten guild rules were applied less and less, thus the guilds were cancelled by their own in this period.

Certain crafts completely vanished by further development of industry and the market, and modernization during the twentieth century, while those that survived had to adapt their way of working to the time and demands of the market.

It must be admitted that there is significant number of old craftsmen in the Bascarsija, who, despite all setbacks, succeeded to preserve traditional appearance and offer of their products.

There are also a few of those who have retained only craft's name and store window, but in fact they deal with something completely different. Something like this must not be blamed, because the craftsmen earn their living in their shops, and they cannot sell decorative silk ribbons and buttons and other things when no one is buying them any more. Most of craftsmen, however, have adapted to the time within their own craft.

The only way to preserve the old crafts and enable craftsman normal life from production of traditional goods can be achieved through cooperation between the craftsmen and authority institutions, museums, bureau for protection of monuments and the association of old crafts.

Only together we can achieve so much, we can clean the Bascarsija from everything that is not traditional and urban, and in this way influence on formation of consciousness and tastes of local and foreign customers. In the same time, the Bascarsija is always ready to provide various services, repairs and advice which cannot be found anywhere else.